State machines as the source of truth in a team

-

Stefanos Lignos

Stefanos Lignos - Modified Su Aug, 2024

Some time ago, I wrote this article Working with State Machines in Angular . (If you don’t know what a state machine/statechart is, I would suggest to have a look at this article first)

My main focus in that article was to explain how we can reduce the complexity in a reactive system by using state machines. In addition, I tried to explain how we can create and use state machines in an Angular project using a library called XState. In this article, I want to focus more on a topic I clumsily touched at the end of my previous article. In the last paragraph I wrote:

In my ideal world, the Business Analyst would be responsible for drawing up the state machine configuration as part of the task specification and this state machine would be committed on GitHub or BitBucket ready for revision and part of the actual implementation process. In this way, the team would talk the same language and we would be able to avoid most of the misunderstandings.

One of the major issues every development team experiences is miscommunication between its members. In a development team we have people from different backgrounds and areas of expertise. We have people using different vocabulary. Team members using technical terminology, who can give a detailed explanation of the internal workings of a system and others who see it as a blackbox. All of them approach the same problem from a different point of view. However all these people have the same goal. The goal is to provide a system which has a specific behaviour for the end user. In this article we’re going to explore how we can create a shared visual language for the whole team by using state machines and statecharts. We want the team to have a common source of truth to describe the behaviour of the system they’re building. One of the reasons I feel I can focus more on this topic now is the latest tools the team behind XState (stately.ai) has released recently.

Looking back upon the creation of Statecharts

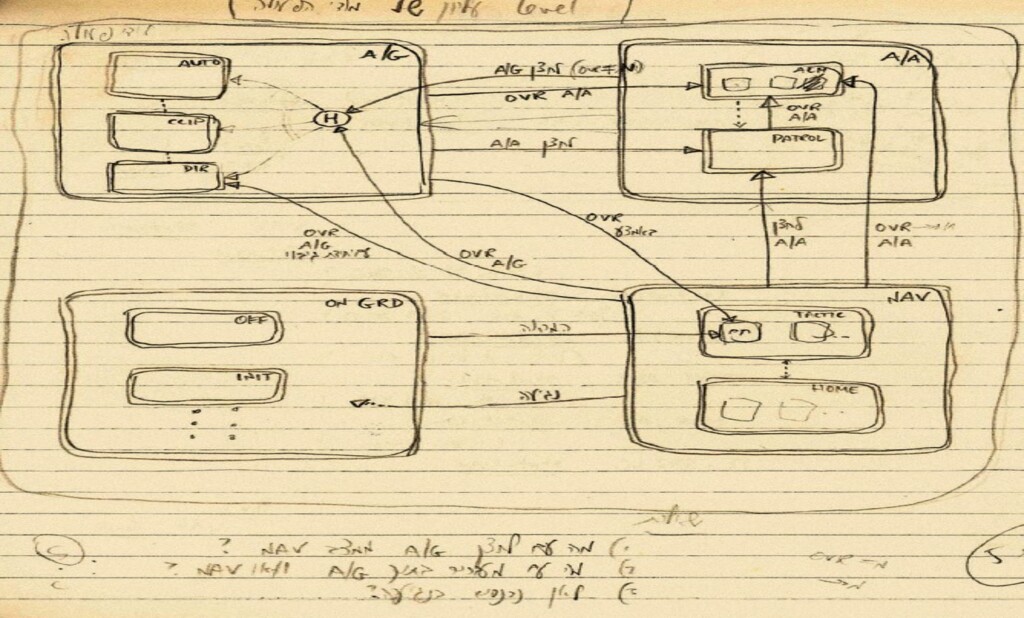

Before we dive into the topic of this article, let’s go 40 years back. This is when the Computer Scientist David Harel invented the language of Statecharts. As he describes in his paper “Statecharts in the Making: A Personal Account”, in 1982 he was asked to consult for the Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) which in that period was trying to build a home-made fighter aircraft and the project was facing some serious issues. Working with all these talended engineers in IAI, he realized very soon that the main issue they had was basically the difficulty of explaining in simple words the behaviour of the varius systems they were trying to build. Their source of truth was a two-volume document of 2000 pages each, written from different people, from different perspectives.

It seemed extraordinary that this talented and professional team did have answers to questions such as “What algorithm is used by the radar to measure the distance to a target?”, but in many cases did not have the answers to questions that seemed more basic, such as “What happens when you press this button on the stick under all possible circumstances?”.

David Harel, Statecharts in the Making: A Personal Account

The fighter aircraft the avionics team was trying to build is a perfect example of a fully reactive system. An event-driven system with an event-response nature, including strict time constraints and parallelism. The main challenge in these kinds of systems is to provide a clear yet precise description of how the system should behave. To specify its behaviour in a language understandable to every member of the team. In a language like this the most fundamental part is the notion of State and how we transition to another state based on an event (e.g “When the aircraft is in air-ground mode and you press this button, it goes into air-air mode, but only if there is no radar locked on a ground target at the time”). One mathematical model of computation to descibe transitions between states based on events is the Finite State Machines. Harel, took them one step further by introducing the notion of hierarchy and concurrency so we can describe the behaviour of complex reactive systems with them.

Coming back to the present

A lot of the web apps we build nowdays embrace or should embrace the following four traits as they defined in the The Reactive Manifesto. They are:

- Responsive —React to users

- Scalable —React to load

- Resilient —React to failure

- Event-driven

And like the avionics team, most of the teams building reactive systems nowdays experience challenges for the same reason. The difficulty of describing the behaviour of a reactive system in a way that is precise and cannot be misinterpreted by its members.

Working without state machines

Let’s see how a team would communicate without using state machines and examine an example of a miscommunication within the team. In this example, the team builds a secure mail platform. In the current sprint the Business Analyst has introduced the following story:

As a User I want to be notified when my email contains sensitive data so I avoid an accidental data leak.

Acceptance Criteria:

- The user will be notified when he tries to send a message to a user in a different domain and when there are sensitive data in the “Subject” or the “Body” of the email.

- There is a toggle button with the label “Secure”.

- We notify the user when there are sensitive data in his email only when this button is enabled.

Based on how this story is written, the solution from the developer would be that when the toggle button is enabled, for every change we validate the email and if there are sensitive data in the mail we show a notification.

In the next sprint the Business Analyst introduces the following story:

As a User I want to be prompted to enable the secure toggle button when my email contains sensitive data so I avoid an accidental data leak.

Acceptance Criteria:

- The user will be prompted to enable the secure toggle button when he tries to send a message to a user in a different domain and when there are sensitive data in the “Subject” or the “Body” of the email.

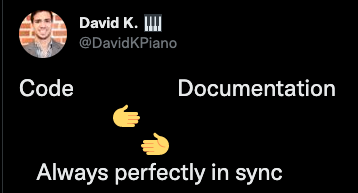

Only now, after one sprint, the developer understands that the logic he implemented in the previous sprint was wrong. The mail data should be validated not only when the toggle button is enabled but also when it is disabled. Now he will have to change his code and some of the work he did in the previous sprint is not valid anymore. This change might be trivial in this example but it makes more visible the main issue in this development approach. The Business Analyst and the developer have a different source of truth. For the Business Analyst the source of truth is the board with the tickets and for the developer it is the codebase. It’s really hard to keep these two sources in sync. Here is a tweet from the creator of XState on the same topic:

Also keep in mind that in a team we don’t have only the BA and the Developer. We also have the UI/UX people with a different source of truth, Figma for example, the testers with an excel sheet or another source where they keep all the possible scenarios they can think of and so on and so forth.

How can we make sure that a team has only one source of truth? How can we make sure that the requirements for a story are in sync between the team members all the time?

Using statecharts as the source of truth

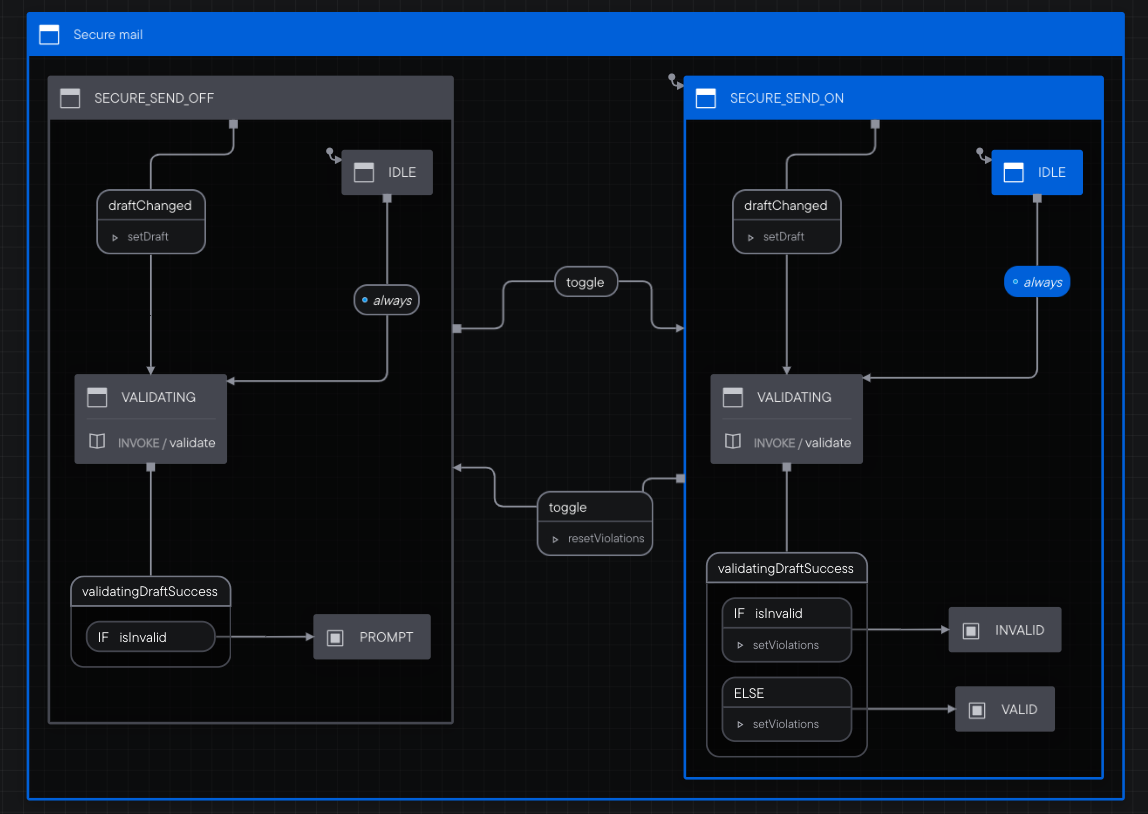

Let’s see how we can avoid the problem we mentioned in the previous paragraphs by using a shared visual language like statecharts in the development process of the team. The BA apart from writing the story, would use the new tool released recently from the team behind the XState library. This tool is the Stately Editor, a drag-and-drop visual editor which you can use to build the business logic of an app, feature, etc. For the stories we described above, the BA would draw the following diagram (you can play with this diagram and simulate the business logic here ).

The next step would be the developer using the configuration for the state machine which can be exported from the editor directly to his code. This is the exported configuration.

{

"id": "Secure mail",

"initial": "SECURE_SEND_ON",

"states": {

"SECURE_SEND_OFF": {

"initial": "IDLE",

"states": {

"IDLE": {

"always": {

"target": "VALIDATING"

}

},

"VALIDATING": {

"invoke": {

"src": "validate"

},

"on": {

"validatingDraftSuccess": [

{

"cond": "isInvalid",

"target": "PROMPT"

},

{

"target": "VALID"

}

]

}

},

"PROMPT": {

"type": "final"

},

"VALID": {}

},

"on": {

"toggle": {

"target": "SECURE_SEND_ON"

},

"draftChanged": {

"actions": "setDraft",

"target": ".VALIDATING"

}

}

},

"SECURE_SEND_ON": {

"initial": "IDLE",

"states": {

"IDLE": {

"always": {

"target": "VALIDATING"

}

},

"VALIDATING": {

"invoke": {

"src": "validate"

},

"on": {

"validatingDraftSuccess": [

{

"actions": "setViolations",

"cond": "isInvalid",

"target": "INVALID"

},

{

"actions": "setViolations",

"target": "VALID"

}

]

}

},

"INVALID": {

"type": "final"

},

"VALID": {

"type": "final"

}

},

"on": {

"toggle": {

"actions": "resetViolations",

"target": "SECURE_SEND_OFF"

},

"draftChanged": {

"actions": "setDraft",

"target": ".VALIDATING"

}

}

}

}

}How we can create a statechart with this configuration can be found in the documentation of the XState project. An example of implementation in Angular can be found on this Github project.

We can already see the benefits of this approach. Every time the BA or the developer makes a change at the editor, this change automatically is applied in the actual implementation of the business logic in the codebase and vice versa. Every time the BA creates a diagram in the editor, at the same moment he creates the documentation. In reality he creates a shared visual language, a common source of truth for the bussines logic for the whole team.

What about the QA?

We created a source of truth for the whole team. We saw how we can do this by using the Stately editor(BA perspective) and the XState library which translates the output of the editor to a state machine (developer perspective). But what about the QA people? Apart from having a better understanding of the business logic because of the visual representation of the business logic, do they benefit in any other way?

The main problem the QA engineers have in a dev team is how to keep up to date the testing scenarios with the actual implementation and with the user story. We already saw how this problem is solved between the BA and the devs. For the QA, we can do exactly the same thing due to another package in the XState project (xstate-test). Using this package we can introduce the model-based testing strategy. Model-based testing is a software testing technique where the behavior of software under test is checked against predictions made by a model. A model is a description of a system’s behavior. In our case we can use the state machine, our source of truth, as a model from which we can generate automatically all the possible test scenarios since we can define deterministically all the possible paths (all the possible user actions - behaviour) that can be followed in the state machine.

Because this is a big topic on its own, stay tuned for the next article where we’re going to focus more on how we can introduce model-based testing using our state machines and Cypress.

Bibliography

[1]:David Harel, Statecharts in the Making: A Personal Account http://www.wisdom.weizmann.ac.il/~harel/papers/Statecharts.History.pdf